The Alzheimer’s Method of Art Making

Annie Abdalla have an MFA in Interdisciplinary Art from Goddard College and a Masters in Environmental Studies from York University; She has also studied interdisciplinary art at Naropa University and the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design. Since 2004 she has been on faculty at Goddard College in the Individualized BA Studies program. She lives by the ocean in Nova Scotia with her furry companion of many years, Miss Maddie.

As a child I spent lots of time looking at the ceiling wondering what a room would look like upside down. This informs my current practice in that my paintings often defy still life traditions by releasing conventional notions of weight and space.

The common artifacts of life – the kinds of scenes or objects that are so commonplace that they become somehow invisible over time, that’s what really seduces me. I often explore for months, or even years, with the same shapes, as if in an ongoing dialogue. These investigations are shaped by contemplative practices that cultivate the ability to perceive with fresh eyes each time. My years of training in Shambhala Buddhism are woven into the work.

As an interdisciplinary artist who, like most artists in Canada, also has a second job. I share with many artists that daily struggle to juggle my other paid work with my arts practice and try to share the manifestations of my creative activity with others as often as possible. In the recent past I’ve had some good invitations to exhibit and publish.

But my already complex formula for pursuing my art and paying my bills was altered for five years as I spend part of each year caring for my mother, in her 90’s, who had Alzheimer’s. I shared this job with my sister, each of us taking turns every few months. I moved from my home in Nova Scotia to spend about six months a year in Sherbrooke Québec.

Maintaining a rhythm in my art practice, turning my mind to the work each day, was always well…up and down. In the beginning I was responsible for my mother’s daily physical care but as her needs increased and her health deteriorated, it was clear that we had to find more help. Fortunately we found an excellent place for her in a nursing home, but my siblings and I all agreed that we would continue to support her quality of life by being here with her every day.While I was in Sherbrooke I had to make-do with studio space that has sometimes in a spare bedroom, and sometimes is just a kitchen table. After a few failures I managed to choose my projects according to the space I had available.

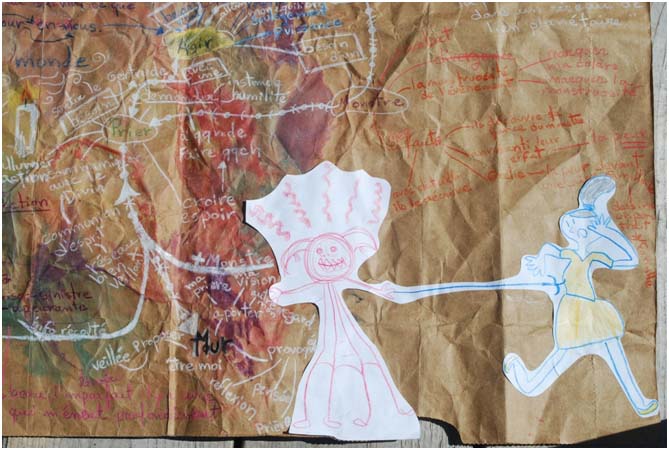

But as I struggled to maintain my arts practice I was been blessed with an auspicious “artful experience” with my mother. She never remembered what she had for lunch, but could still “make with the hands”, and in fact, this is what still made the most sense to her. Every evening when I visited her we went to the living room and set up a little card table and did craft projects. We played music that she could still remember from the years of WWII and we sang along, and every so often we get up to dance to a favourite tune.

We stencilled wooden trays, made fabric books using iron-on adhesive, and made dozens of plaster cupcakes with lovely spackle icing and sprinkles for the nursing staff. We painted flowerpots, built clay vessels, and made boxes in which to deliver cookies to friends. She never remembered a project that we’d done so I could bring the successful ones back over and over and she loved them just the same.

The things that we made were nothing like the art that I make in my own studio. But something really surprised me about how all this time doing “handicrafts” has affected my own practice. Somehow this daily experience of making with the hands has kept the system “greased” and I have experienced a particularly good flow of artistic energy. I’ve had some rather fruitful years even.

I liken this experience to my parallel practice of Shambhala Buddhism and the years that I have spent training my mind to have a kind of attention to the moment. Central to that practice is the notion of path with no goal, something that is quite foreign for our Western minds that are always making plans, setting objectives and striving for goals. I have spent many years cultivating the skill of paying attention to my own body, speech and mind. This is the primary frame of reference I have for the concept of a practice – it is something worth doing even when the immediate results are invisible. It takes patience, and a release of the idea of always “getting somewhere” or “producing something” and it requires regular engagement.

I have recently come to understand that at its core my art practice has a physical experience that is irreplaceable. I cannot simply think about making art and then go into the studio and do it – I need to train my body in order to be able to come back day after day to this kind of engagement. I need to keep the “art blood” flowing, the system greased. What has really surprised me is how effective these crafty projects have been as a training path. I’m beginning to understand that it doesn’t matter how I cultivate that flow – eventually something interesting will catch fire in my heart and my hands and new work that challenges and pleases me will emerge.

Would I be satisfied to just paint flowerpots for the rest of the year – probably not. But I’ve came to really appreciate the quiet time that I had with my mother watching her have successful cognitive experiences. In this situation I simplified the environment as much as possible, I tried to pay attention to what was happening in the moment without judgement and, most importantly, I slowed down. The outcomes, the things we made, were inconsequential, and are largely forgotten. We let go of them without attachment.

When I returned home to my own studio space I found myself brimming with new ideas and ready to work. Like an athlete who has been training for the day of competition, I have a muscle memory of how it feels to be making something and paying attention to the process.